Stress

Ready, Set... Relax

Better rest, recovery, and repair would make for a better world.

Posted November 29, 2018

Modern, first-world life is a bit of a paradox. We can fly and have calculators and streaming entertainment and all sorts of interesting facts at our fingertips almost anywhere we go. We have super comfortable jersey sheets and foam pillows and carpet and heating and air conditioning. But despite all these amazing things, many designed specifically for our comfort and convenience, we are stressed out. I feel it especially, of course, in the people walking into my psychiatry clinic, but you can see it at the grocery store, at town meetings, airports, highways, work, even at the gym… stress rolling off people in a bad miasma. Angry faces, rude gestures and words, and bad feelings. We get going in the morning with stimulants and tone down at night with alcohol and pot.

Stress isn’t all bad, of course. Exercise is a form of stress on the cardiovascular system and the muscles. Applied in the right amount, you get stronger and faster. Too much and you get injured. Emotional stress is similar: Successfully facing a fear or a tough situation makes you more resilient, but apply too much emotional stress and you get broken down. In a psychiatry clinic, we see the clinical anxiety and depression that arises from way too much stress. Physiologically we call it an aberration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, fancy talk for the stress response being turned on for too long, resulting in the stress response no longer working properly. Under normal circumstances, the adrenal glands produce cortisol in the morning that gets you up and ready to face the day. In clinical depression, the cortisol response is a dragging feeling of dread, heavy limbs, suicidal thoughts, and/or hopelessness. In clinical anxiety, cortisol can wake people up with a panic attack.

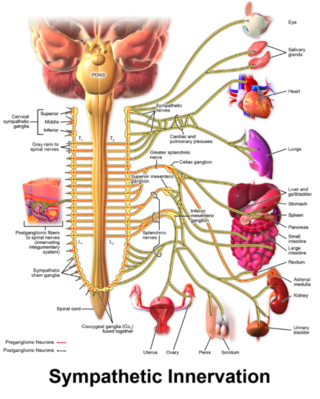

Taking it back a step further, we have two autonomic nervous systems that do their thing without us having to think about it. First is the sympathetic, “fight or flight” nervous system. This is the system that fires up the cortisol and adrenaline responses. Usually this is good: Heart rate and blood pressure go up to support that workout; dopamine and the right amount of adrenaline can help you concentrate to get a project done. But in physiology, there is always a balancing act. Sympathetic tone is counteracted by the parasympathetic, “rest and digest” nervous system. The parasympathetic system quiets the nerves, slows the heart rate, brings down blood pressure, and sets the stage for recovery and repair.

You can see the two opposing systems in action just by breathing in and out, slowly, while checking the pulse at your wrist or neck. Breathe in, and the air in your lungs squishes the parasympathetic fibers in the vagus nerve that runs down from your brain through your chest to your abdomen. Your heart rate speeds up. Breathe out and hold, the vagus nerve parasympathetic tone is restored, and your heart rate will drop. Greater heart rate variability, the difference between that rate when you breathe in and when you breathe out, is a sign of general good health and good parasympathetic tone. It’s not surprising heart rate variability drops in cardiovascular disease, stress, depression, and overtraining.

There are other fancy ways to measure sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. EEGs can show the activity in different parts of the brain that control the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Galvanic skin resistance is a measure of changes in sweat gland activity that reflects the intensity of emotional arousal. A higher number means your skin is drier and has more resistance to the flow of electricity, a lower number indicates more sweat, and, in controlled circumstances, more stress.

Part of my job, then, when faced with the army of stressed-out individuals walking into my clinic, is to help people increase their rest, recovery, and repair. To do this, I need to help them increase parasympathetic tone. There are all sorts of low-tech ways to rest and recover. Therapy to help with coping and increase resilience. Regular exercise, but not too much or too hard without sufficient recovery. Yoga or meditation or at least enough restful sleep. Simplifying life by getting rid of clutter and making it easier to take care of the household and keep things orderly. Direct breathing interventions to help people get through panic attacks. Reducing alcohol, which is relaxing while it’s in your system but wrecks sleep and causes anxiety as it’s metabolized out. Eliminating stimulants and activity or activating light too late in the evening. Self-care and increasing parasympathetic tone is a part-time job all on its own, but vital for people with clinical anxiety and depression.

This being the modern world, there are all sorts of gadgets and technologies to increase parasympathetic tone without the work of active yoga or meditation. Fitbit and smartwatches will remind you to move enough and rest enough. In our clinic, we use the alpha-stim, a cranial electrostimulation device used for insomnia and anxiety. I’ve seen heart rates and blood pressure drop precipitously in anxious people using the alpha-stim even if they don’t feel it’s doing much for their anxiety at the time. There are other companies like NuCalm who have designed an entire system of physiologic inputs to maximize the parasympathetic response, used at dentists offices to calm anxious patients and by professional athletes to promote effective and efficient recovery for maximum performance.

Are we going the wrong direction, adding more technology when we could just sit and breathe with our eyes closed? I’m a psychiatrist, not a philosopher—I just want strategies that are accessible, are not harmful, and work. Often, people don’t like to meditate, as sitting and breathing and continuously clearing the mind is hard work, especially when you are busy and stressed. Changing work/life balance and simplifying could help, but society doesn’t appear to be going that direction any time soon. However we can achieve it, a more resilient, recovered, well-rested population of people would make for a whole different modern world.

Copyright Emily Deans MD