Ketamine

Esketamine for Depression: New FDA Approval, New Controversy

A new medication may have good potential but serious risks.

Posted July 3, 2019

A few months ago, the FDA approved a new formulation (an enantiomer) of ketamine, delivered as a nasal spray, for treatment-resistant depression. The drug must be administered in the doctor’s office with a required observation period of two hours to monitor vital signs and other side effects. The recommended dosage schedule is twice a week for four weeks, then once a week for four weeks, then either once a week or once every two weeks for…well, no one really knows.

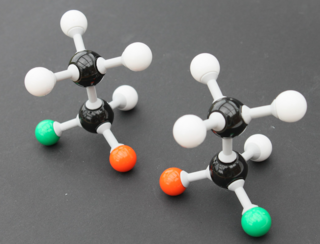

Quick biochem lesson, don’t worry, it’s simple but important: When you make drugs in a lab, you often end up making both right- and left- handed versions of the molecules; they are mirror images of each other, but just as your left hand won’t fit into a right glove, a right- or left-handed molecule may or may not activate or block a different receptor.

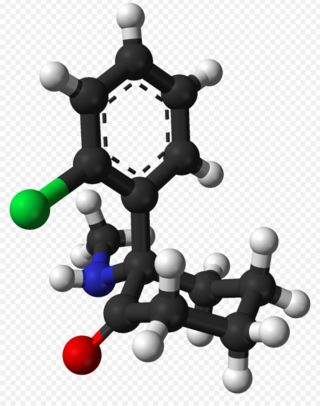

The two enantiomers (mirror images) are S and R ketamine. Traditional intravenous or intramuscular ketamine in the US used for anesthesia is a mix of both enantiomers; esketamine the nasal spray is just the S version. There are various forms of ketamine with different ratios of S and R.

Ketamine and esketamine have several mechanisms of action, the most important one being as an NMDA antagonist, which means it shuts off a neurotransmitter system that seems to be torqued to the max in several different psychiatric disorders, including clinical depression. Lots of medication and therapies facilitate recovery and repair from a chronically turned on stress response and subsequent cascade of neurotransmitters, but very few things get right to the point and intervene where the gas petal hits the metal, like where ketamine stops glutamate from turning on the NMDA receptor.*

What does that mean for depression? Well, ketamine works fast. It can work almost immediately. Doctors who work in ketamine clinics and patients of mine who have tried a ketamine clinic have described a lifting of depression symptoms within 30 minutes to a couple hours of administration.

In the latest study, by Popova et al in the American Journal of Psychiatry, testing antidepressant + esketamine + antidepressant + saline nasal spray placebo, the esketamine arm separated from placebo by 24 hours. There was still some clinical improvement over placebo at four weeks, but it was a mild effect compared to placebo. This finding follows what we’ve heard about ketamine for 20 years: Wow, it works fast—but does it last?

What about side effects? About 20-25 percent of patients in the treatment arm had dizziness, nausea, dissociation (in this sense, a floaty feeling of not being in your own body), vertigo, and altered sense of taste. These faded by about 90 minutes. The treatment also raised blood pressure, peaking at 30 minutes, which also went back to normal by two hours. Headache, sedation, anxiety, and vomiting occurred in another 10-20 percent of patients (though 17 percent of placebo patients also got a headache).

All in all, the side effects were a deal breaker for 7 percent of the esketamine subjects. At the end of the study, the patients were monitored for rebound depression, suicidality, cravings for esketamine, and other symptoms of withdrawal. None were observed at 1-2 weeks after cessation of the drug.

If you look at the pooled data on esketamine that was presented to the FDA, published in February of 2019 (scroll to page 52), you can see that in all the esketamine trials, some of which were in very seriously ill, hospitalized, suicidal patients (we don’t get a whole lot of antidepressant trials with patients this ill), there were three completed suicides in the treatment groups in a 4-20 day period after cessation of ketamine. I’d be interested to see any safety monitoring data from the (likely hundreds) of off-label ketamine clinics that are being run in academic medical centers and elsewhere on rebound depression and suicidal ideation. Was this withdrawal? A sad consequence of a serious illness? We don’t really know.

JAMA Psychiatry also released a paper earlier this month that looked at longer-term treatment with esketamine. This study took 297 patients whose depression responded to esketamine + antidepressant and enrolled them in a randomized discontinuation phase after 16 weeks of treatment. Half continued with esketamine + antidepressant, the other half a placebo nasal spray and antidepressant, and were followed for about two years. Here the differences got quite significant: Continuing esketamine decreased risk of relapse of depression by 50-70% compared to placebo. Half of the relapses occurred in the first four weeks after stopping esketamine.

Ketamine and esketamine are big guns in the treatment of resistant depression, with a record of helping some seriously ill people that did not respond to other interventions, which is not unexpected in a medication that has a new mechanism of action. However, there may be some significant risks associated with the treatment.

More data about long-term effects and discontinuation effects are needed. It’s my guess that the people who are diagnosed with treatment resistant depression are a conglomerate of people with many different biologic, psychologic, and genetic profiles, and as we learn more about the multitude of complications leading to treatment resistance, we will be able to more specifically titrate treatments. As always, prevention in the general population—with public health measures encouraging regular exercise, a healthy whole-foods diet, sufficient and restful sleep—could safely help more people. But for those with treatment-resistant depression, we need as many options as we can get.

* Ketamine and esketamine have *many* other mechanisms of action. Some formulations and ratios of the S and the R do different things. Besides NMDR blocking, they have actions at opioid receptors, other neuroamine receptors, and cholinergic systems. What does that mean? Well, it’s complicated. But what it comes down to is ketamine is a short term anesthetic and drug of abuse at higher doses (causing euphoria and dissociation). The antidepressant doses are lower than anesthetic doses.

Copyright Emily Deans MD